The result was the start of political and ideological American Revolution, developed into American War of Independence, which finally observed establishment of the first modern liberal democracy in the world- United States of America.

Though the American Revolution and American War of Independence are generally observed as a single event, to study it properly we have to divide it into two phases:-- Developments before 4th July, 1776; till the Declaration of Independence.

- After Declaration of Independence, from where the American Revolution entered into a full fledged war to become American Revolutionary War or American War of Independence.

What Happened Right Before the American Revolution?

The American Points of View

The remarkable material and cultural progress of the British American colonies during the middle decades of the 18th century was accompanied by the growth of a new kind of self-assurance. They were developing a way of life of their own which made them more than merely transplanted Europeans.

This new spirit was very evident in the newspapers and other political writings of the 1740’s and 1750’s. Surveying their past achievements and future prospects, many Americans felt that they were fully capable of controlling their own destiny.

This self-assurance was not at first accompanied by any desire to repudiate British heritage or the British political connection. Almost all colonists wished to remain within the British Empire for both, sentiment and material interest. But some of them started to feel that they were entitled to full self-government and equality similar to the people of Britain.

They also felt that the affairs of British Empire should no longer be administered so exclusively for British advantage. Forward-looking men like Benjamin Franklin dreamed of a perpetual partnership of the English-speaking peoples in which leadership might eventually pass to the western side of the Atlantic.

Certain kinds of people, particularly those who were more enterprising and ambitious, were especially influenced by this new spirit. For example, the more vigorous of the southern planters were eager to escape from their burden of debt to British merchants, and hopeful of finding new opportunities in the settlement of the rich lands across the Appalachians. The more energetic Northern merchants felt that their expanding business activities were restricted by the British system of trade regulation and the British limitations on colonial manufacturing.

Conflict on these issues had been prevented before the 1770’s only because many of the trade laws were inadequately enforced and the merchants were able to violate them with impunity.

Meanwhile many of the urban mechanics and some of the farmers were demanding wider economic opportunities and more political rights. They wished to end the special privileges of the colonial ruling classes and bring about more political and economic democracy. However, they found that these ruling classes were supported by the British officials in America and the British Parliament in London. This made the struggle for colonial democracy to become a struggle for colonial self-government.

These were the groups, mentioned above, who took the lead after 1763 in asserting American rights and finally in establishing independence. Therefore, the American Revolution was a complex struggle with two objectives:-- It was partly a revolt of planters and merchants against the restrictions imposed upon American economic growth by British mercantilism.

- On the other hand, the American Revolution was partly a revolt of farmers and mechanics against aristocratic privilege.

To a considerable extent, of course, these two movements pointed in different directions. Throughout the Revolutionary period there were conflicts between upper-class and democratic elements within the colonies.

By no means all the people of the colonies shared these sentiments. Probably a majority of the farmers took no interest in politics. Among the richer classes there were many who were content with things as they were. They were more afraid of democracy in America than of British control. When American War of Independence emerged, a large part of such Americans remained apathetic, while many of them actively supported the British Government.

The British View

While a new spirit and self-awareness was developing among American colonists, the British still adhered to the prevalent mercantilist theory. According to the theory they believed the colonies existed primarily for the benefit of the home country and therefore, must be kept in subordination.

They did not recognize any limitation upon the power of British parliament, nor did they allow much opportunity for self-governance to the colonists. From the very beginning till the end, the British administration in American colonies did not share the American belief that Parliament’s authority was restricted by some kind of fundamental law.

There was a little number of British political leaders, such as Edmund Burke and the Earl of Chatham who felt that it would be unwise to make any change in relationship as it had existed before 1763 between the British and Americans. But most of others started to believe that the colonies ought to be more strictly supervised.

As a result of the French and Indian War (1754-1763), Great Britain had earned a much larger American empire to govern. Britain also had earned a heavy war debt. Therefore, it seemed desirable to many British officials to reorganize imperial administration, requiring the American colonies to pay part of the cost of imperial defense. It seemed necessary for the British government to resort to compulsion. Because experience during the war had shown that the colonies were very reluctant to cooperate with each other for mutual protection and to pay any additional taxes.

Meanwhile, it was notorious that the trade regulations were habitually violated by the colonists. British merchants were complaining of colonial competition and of colonial trading with the enemy during the war. This situation called for action to prevent smuggling.

From their own point of view British governments after 1763 were not acting illegally, nor were they trying to reduce the Americans to slavery. But they were seeking to hold the colonies in their traditional position of subordination. However it was just at the time when the most vigorous elements in the colonial population were beginning to feel themselves entitled to equality, and had been making themselves ready to take this by force, if needed.American Revolution Causes

The American Revolution was not an outcome of a single event or cause. Rather there were several major events and historical developments that led up to the American Revolution. However, at first even the founding fathers of the United States of America did not imagine that the struggle of British American colonists for imperial equality would soon turned into a revolution and then the War of Independence. But the contemporary political developments and policies imposed by the British government, especially from the middle period of French and Indian War had paved the way for one of the greatest historical event in history to be witnessed.Contemporary British Politics | American Revolution Causes

In view of the fundamental differences between the British and American conceptions of the nature of the Empire and the powers of Parliament, it seems unlikely that conflict could have been avoided permanently. However, the lack of statesmanship in London during the 1760’s and 1770’s was an important contributory factor in precipitating the American Revolution.

For a long time prior to 1760, Great Britain had been governed by cabinets representing the majority party in the House of Commons rather than by the king. But the year 1760 marked the accession of King George III. The King was a young man who was by no means willing to remain a mere figure head. He had a few of the qualities needed for governing an empire. But he was pertinacious and hardworking. On the other hand the unusual virtue of his private life made him very popular among the middle classes.

He set out to win control over Parliament by undermining the dominant Whig party and by building up a body of personal adherents. The first decade of his reign was a period of political instability. There were frequent changes of government and nobody stayed in power long enough to work out and administer an effective colonial policy.

By 1770 King George had succeeded in his objective. For the next twelve years he remained the effective head of the British Government with appointing Lord North as British Prime Minister, who usually followed his advice. On the other hand there was “the King’s friends”, who used to control the House of Commons in that period.

Liberal Englishman have always blamed George III for the American Revolution. But this is not wholly fair. Because the King was not responsible for the initial attempts to tax the Americans, and the fundamental issues at stake went deeper than any question of personality.New Colonial Land Policies | American Revolution Causes

The first move towards tighter British control of the colonies was made before the end of the war with France. Since many colonial merchants habitually evaded the regulations which prohibited trading with enemy, customs officials were given writs of assistance or general search warrants. This empowered the officials to search ships and warehouses for smuggled goods. This aroused vigorous opposition, especially in Boston, where the lawyer James Otis defended the merchants with great force and eloquence.

According to Otis, the writs of assistance violated the fundamental rights of British citizens and were therefore illegal. This argument reflected the American conviction that the powers of the British government were limited by fundamental law.

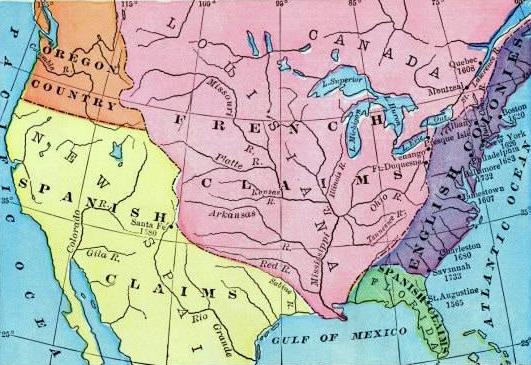

|

| North America before French and Indian War |

At the end of the war the most immediate problem confronting the British authorities was a decision about the disposition of the trans-Appalachian territories from which the French had now been expelled. On the one hand, the land was claimed by several of the colonies, particularly by Virginia and a number of colonial land companies. All of them were in conflict with each other. They were hoping to secure titles to parts of the Appalachian and organize settlement.

On the other hand, British fur-trading companies were planning to take the place of the French at Montreal. They wanted agricultural settlers to be excluded and the territories reserved for their own activities. Meanwhile, there were a number of Native tribes in the region. Some of them had recently participated in the Pontiac rising and needed careful handling.

|

| North America after French and Indian War |

Reconciliation of these conflicting interests was obviously a complicated problem. So, in 1763 the British government issued a proclamation prohibiting any settlement beyond the Appalachian watershed. This was intended merely as a temporary measure while British officials studied the question and worked out a program of expansion.

During the next few years British officials made progress in negotiating treaties with Native American tribes under which lands were to be opened for white settlement. The proclamation line was moved further to the west in 1768.

Meanwhile, the agents of colonial land speculators hopefully continued to lobby in London for validation of their titles. But the British government was slow to reach any decision of these questions, partly because of the influence of the fur-traders and of groups at home who argued that colonial western expansion was contrary to British economic and political interests.

The delay exasperated influential groups in the colonies, especially in Virginia. It made them feel that the whole western question could be left to the Americans to handle by themselves instead of being controlled by British officials.

Their resentment became more acute in 1774 when the Quebec Act declared all the lands north of the Ohio to be part of the province of Quebec, and thus wiped out the claims to the region of several of the colonies.

The Grenville Measures | American Revolution Causes

One of the acts of trade which American merchants most consistently violated was the Molasses Act of 1733. According to this act a duty of sixpence a gallon was to be paid on molasses bought from the French and Spanish West Indies. The purpose was to compel American merchants to buy the product solely from the British planters.

Since the French and Spanish trade was extremely profitable, effective enforcement would mean serious losses to the merchants. However, British Prime Minister Grenville decided that this might be a source of revenue. In 1764 he put through Parliament the Sugar Act. The act reduced the duty on foreign molasses from sixpence to threepence. He also set up machinery by which the duty could actually be collected. Duties were also imposed on some other colonial imports.

This unpopular Sugar Act was followed by the Stamp Act in 1765, which declared that stamp duties were to be paid on newspapers and legal and commercial documents. Grenville calculated that these measures would bring in about one-third of the cost of the army stationed in America. Although some indirect taxes had been a part of the system of trade regulation, this was the first time that any British government had laid direct taxes on the colonies.

The measures resulted in popular uprising and violent protest throughout the British American colonies, with the implementation of Stamp Act. But it was the boycotting of imported goods that carried out heavy financial losses for both, British government and traders. As a result, in March 1766 the Rockingham government replaced the Stamp Act, lowering the molasses duty one penny, to be paid on all molasses, British as well as foreign. They also passed a Declaratory Act affirming the principle of Parliamentary supremacy over the colonies.

Delighted with their victory, the Americans enthusiastically asserted their loyalty to the mother country, and paid no attention to the Declaratory Act for a time being. But the colonists had already learned how to gain their right forcefully if there would be any necessity in future.

The Townshend Duties | American Revolution Causes

Parliament reduced taxes in England. So Townshend, with a deficit to make up, turned to the colonies. In 1776 a number of new duties were imposed on colonial imports. New administrative machinery was set up to make sure that they would be paid.

The Townshend duties remained in force for three years. The period witnessed incident like Boston Massacre of 1768, which made it clear that the American Revolution had already started and was only waiting for a war to be started to decide the fate of American Colonists and British Empire.

The Final Causes | American Revolution Causes

The British Government made its next and most crucial mistake in 1773. The East India Company was in financial trouble, and its stock-holders, who included some very influential men, demanded assistance from the government.

Since the company had a large supply of surplus of tea on its hands, Lord North decided that it should be allowed to ship and sell it directly to the agents in the colonies, paying the small American duty but not the larger duty previously collected at British ports.

Thus the Americans would get their tea at much lower prices and would, it was hoped, drink the company out of its difficulties. Getting tea from the company was not a problem for the colonists. But what made the Tea Act of 1773 unacceptable to the Americans was that the East India Company would acquire a virtual monopoly of the colonial tea market.

According to the plan neither the smuggling nor the law-abiding merchants would be able to sell their tea cheaply enough to compete with East India Company’s tea.

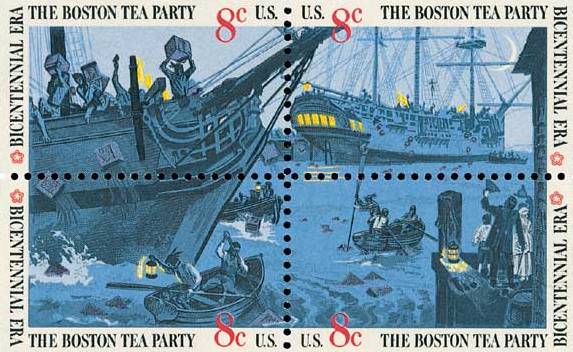

The plan, moreover, was generally interpreted in the colonies as an attempt to bribe them into accepting the principle of Parliamentary taxation. The result was that many of the merchants again joined radical anti-British forces. The effect was that the famous Boston Tea Party occurred.

The King and Lord North felt that this challenge to their authority must be met with a strong hand. Early in 1774 a series of four Coercive Acts were passed; popularly known as ‘Intolerable Acts.’ The most important of these intolerable acts closed the port of Boston to commerce until the destroyed tea was paid for. These also made various changes in the Massachusetts political and legal system so as to increase the authority of the royal governor.

About the same time Parliament also passed the already mentioned Quebec Act. This alarmed the Americans not only because it annulled the colonial claims to the lands north of the Ohio, but also because it provided for an autocratic regime in Canada and gave privileged position to the Catholic Church in the province.

In actuality both of these provisions were in accord with the wishes of the French-Canadian population. But American colonial propagandists seized upon them as proofs that Lord North proposed to abolish all colonial liberties and to promote Catholicism. Thus the Quebec Act was as intolerable as the Coercive Acts to the Americans.Course of the American Revolution

The American Revolution started to gain its clear ground from the end of French Indian war. No doubt, the American colonist had become subjects of suspicion to the British government due to their involvement in smuggling with the contemporary British enemies.

But it is also true that it was due to the British mercantile system. The British government, as well as British people was in no mood to listen the popular American demand for equality. No American merchants were in a position to compete with the British counterparts without gaining equality. But with a hope to gain that equality with equal economic status they definitely involved in some activities, what we can say illegal to some extent only.

Course of the American Revolution

The Opening of the American Revolution

Only a few number of the colonists had a motive to start a great struggle at the end of the Seven Years War or French and Indian War. Most of them thought that the newly acquired lands after the war would be of their agricultural fields for being the people of the land. The British government made the distribution a postponed plan. As a result dissatisfaction among both, the American farmers, plantation owners and merchants started to grow gradually.

The British government of 1763 also decided to, maintain an army of 10,000 troops in North America, in order to guard against possible Native raids and French attempts at reconquest. But a number of colonists thought it a prevention act for American colonists to establish new lands.

This was not totally untrue because on one hand British mercantilism left nothing for American merchants to do except smuggling, but on the other hand on that base the government was discussing with British merchants to leave the lands in their hands. The colonist definitely agreed upon it as an unequal measurement, which was totally against newly emerged American spirit.

The troops were to be posted in Canada, Nova Scotia and New York. Since it was exhibited that they were needed for the defense of the colonies, this led to the momentous decision that the colonies should be required to pay part of the cost.

Course of the American Revolution

The Stamp Act Reaction

When the news of Stamp Act reached the colonies, the indignation seems to have been nearly unanimous. The Americans did not regard a British garrison as either necessary or desirable. Suffering from a chronic shortage of currency from a post-war economic depression, they felt that the act would drain the colonies of money and make their debts to British merchants more intolerable.

The colonists also had learned from the long experience of colonial legislatures in dealing with royal governors, the importance of retaining the power of the purse. Taxation without representation, they believed, was tyranny. While they accepted trade regulation by the British Parliament as legitimate, they insisted that Parliament’s imposition of direct taxes was contrary to fundamental law and natural right.

What was surprising to almost everybody was the violence of the opposition. It took the form not only of resolutions by colonial assemblies, such as the Virginia House of Burgesses, which was carried away by the eloquence of Patrick Henry.

Apart from a collective protest drafted by a congress of delegates from nine colonies, which met at New York at October 1765, general mass of the colonies organized riotous popular demonstrations. Groups composed mainly of urban mechanics, made life miserable for the agents who had undertaken to sell the stamps. Custom collectors and other British officials too faced mob anger.

In Boston the house of Thomas Hutchinson, a leader of the Massachusetts upper class and Chief Justice of the colony was partially destroyed by a mob. These popular demonstrations were alarming some of the colonial conservatives as to the British government.

Calling themselves Sons of Liberty, and led by men like Sam Adams in Boston, Isaac Sears and John Lamb in New York, Charles Thomson in Philadelphia, Samuel Chase in Baltimore, and Christopher Gadsden in Charleston, insurgent farmers and mechanics were to play a prominent role during the events of the next ten years.

The most effective weapon used against the Stamp Act, however, a general agreement to stop importing British goods. British merchants suffered heavy losses and urged the government to give way. By this time Grenville had been succeeded as prime minister by the Marquis of Rockingham. Being a wise person Rockingham had soon repealed the Stamp Act in March 1766 and the colonies remained in peace until the Townshend Duties were imposed in 1767.Course of the American Revolution

The Townshend Duties and Boston Massacre

The Townshend Duties remained in force for three years from 1767. The most effective statement of the American case during this period was the series of Letters from a Farmer, written by a conservative Pennsylvania lawyer, John Dickinson. Dickinson still accepted the right of Parliament to regulate trade, but denied that it could levy any direct or indirect tax.

New agreements were made to refrain from importing British goods. So, in a number of seaports, merchants engaged in illegal trade. Those merchants were protected from custom officials by the Sons of Liberty. Such incidents were especially frequent in Boston, where the richest of the smuggling merchants, John Hancock was closely associated with the popular organization directed by Sam Adams.

In 1768 two regiments of British regulars were stationed in Boston to prevent smuggling. The Sons of Liberty did everything possible to arouse popular hostility to these unwanted guests. Finally on March 5, 1770 some of the soldiers, goaded beyond endurance by snowballs and stones thrown by a crowd of jeering men and boys, used their guns. In this so-called Boston Massacre five persons were killed.

In retrospect, what seems most remarkable about this episode is the moderation displayed by both sides after the event. The Governor withdrew the troops from the city. The soldiers responsible were put on trial, resulted in a fair trial. All were acquitted except two, who received mild penalties for manslaughter.

Townshend Duties were repealed, having only one small duty on tea. Many of the Americans refused to pay the duty, drinking only tea smuggled in from Holland. But the non-importation agreements were abandoned, and a large number of merchants, alarmed by the growth of the Sons of Liberty, tried to prevent any further agitation.Course of the American Revolution

Organization of Committees of Correspondence

It was obvious to popular leaders, such as Sam Adams that none of the basic issues had been settled. These leaders used this period of calm to prepare for the next crisis. Adams was a master of the arts of propaganda. In speeches at the Boston town meeting and in numerous newspaper articles he continued to accuse the British government and its Massachusetts representatives, especially Hutchinson (the Governor of Massachusetts) of all kinds of wicked designs against American liberties.

In 1772 Adams and his associates set up throughout Massachusetts a network of Committees of Correspondence, composed of men who would carry on agitation and, if necessary, organize resistance. This idea was imitated by Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson in Virginia and by similar leaders in other colonies, so that a real inter-colonial political organization began to take shape.Course of the American Revolution

The Tea Act of 1773, Boston Tea Party and Coercive Acts

The Tea Act of 1773 provided the first serious landmark for the American Revolution. The first shipments of tea arrived in the autumn. The popular organizations prevented any from being paid everywhere. In some places captains of the ships agreed to return to England without unloading, but in others there were violent incidents.

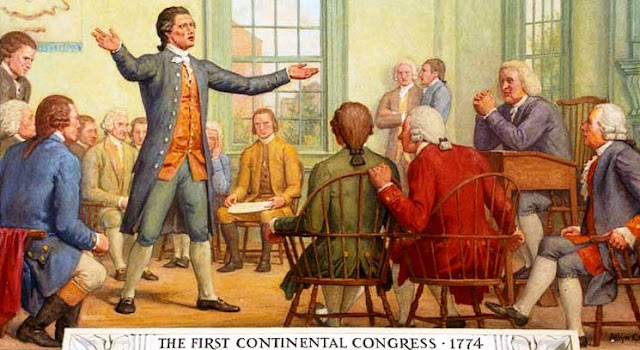

The Virginia House of Burgesses passed a resolution calling for a congress, and the committees of correspondence industriously circulated it throughout the colonies. Delegates were chosen in some cases by the legislatures, in others by self-appointed committees or by mass meetings from every colony except Georgia.

Course of the American Revolution

The First Continental Congress

Numbering fifty-six in all, the delegates assembled at Philadelphia on September 5, 1774. The members of the Continental Congress found themselves divided into two groups.

On one side were the radicals who felt that the time had come for resistance by force. The most prominent of these were the Massachusetts delegates, especially Sam Adams and his young cousin John Adams. Other remarkable persons in the radical camp were Patrick Henry and Richard Henry Lee of Virginia. Most of the radicals had previously been spokesmen of popular opposition to upper-class rule in the colonies.

The radicals won an initial victory when the Congress accepted the Suffolk Resolves, which had been passed by a convention in Suffolk County, the county of Boston town. The resolves declared that America should refuse to obey the Coercive Acts.

This appeared to be an endorsement of armed resistance, and was so interpreted by the Massachusetts delegation. But most members of the Congress were not yet willing recognize that war was inevitable. Instead, they hoped that a commercial boycott would again induce the British government to give way.

It was agreed that Americans should stop all trading with Great Britain. It was also resolved that committees of “safety and inspection” should be elected in every town and county with authority to see that this decision was obeyed and prevent merchants from violating it. This agreement was known as the Continental Association.

The Congress also drafted a Declaration of Rights and Grievances and in order to please the moderates, sent a petition to the King. In these documents the right of Parliament to regulate trade was still accepted.

A compromise proposal put forward by the moderates was defeated by only one vote. This was Joseph Galloway’s Plan of Union. According to the plan a continental government would be set up, consisting of a grand council representing the colonial legislatures and a president-general appointed by the Crown. Authority over the colonies was to be shared between the council and British Parliament.

However, by this time clear-sighted Americans were reaching the conclusion that the real issue was not whether there should be limits to Parliamentary authority over the colonies but whether Parliament should have any authority at all. Perhaps the Americans should be associated with the mother country solely through a common allegiance to the Crown.

This theory had already been suggested by Benjamin Franklin. According to the theory the colonies were entitled to full rights of self-government in the same manner as the British dominions of the 20th century. The early history of the colonies seemed to give it some legal validity, for initially they had received their charters not from Parliament but from the Crown.

In 1774 and 1775 this conception of the status of the colonies was put forward in pamphlets written independently of each other by three of the ablest young men in America:- James Wilson of Pennsylvania, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, and John Adams of Massachusetts. In the final stage of the controversy it was adopted by the Continental Congress.

But, there was of course not the slightest possibility that either King George or any other person of influence in Great Britain would accept this novel view. Even those British leaders, who felt that the British government was to blame for provoking the American colonists, still believed in Parliamentary supremacy over the colonies.

Nor was the King willing to give way after Boston Tea Party. He declared that the time for compromises was past and that the colonies must “either submit or triumphs.” Early in 1775 Lord North proposed that, if any colony would itself contribute money for imperial defense, which to be fixed by the British government, then it would be exempt from Parliamentary taxation. Obviously this proposal did not represent any real concession.Course of the American Revolution

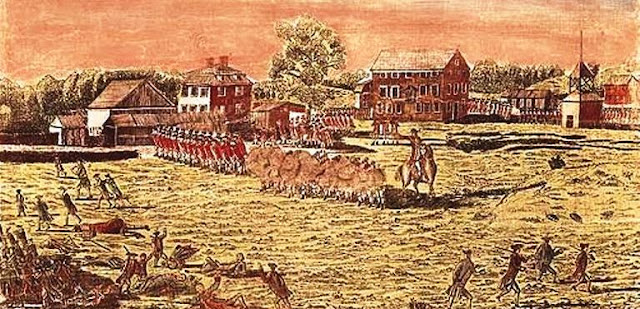

Lexington and Concord | First Armed Conflict of the American Revolution

The Massachusetts delegates came home from the Philadelphia congress assured that they would have the support of the other colonies in opposing the Intolerable Acts. While General Gage and his army occupied Boston the lower house of the Massachusetts legislature reorganized itself as a provincial congress and appointed a committee of safety, headed by John Hancock, to assume executive power and make plans for resistance. Through the winter Gage had control only over the town of Boston, while elsewhere the militia of the colony prepared for war and gathered supplies of guns and ammunition. Armed conflict was clearly imminent.

It began in the early morning of April 19, 1775. Gage sent out a body of troops from Boston to destroy an ammunition dump at Concord and if possible to arrest Hancock and Sam Adams. Two of the Boston Sons of Liberty, Will Dawes and Paul Revere, had ridden out during the night to give warning. As a result, when the British reached Lexington they found a company of militia waiting for them. In the words of Emerson, here was “fired the shot heard round the world.”The British succeeded in reaching Concord and destroying the ammunition. But on the march back to Boston they were attacked by American marksmen from behind walls and houses and suffered more than 200 causalities. After these events some 20,000 men from all the New England colonies gathered at Cambridge, and the British found themselves besieged in Boston.

Course of the American Revolution

The Second Continental Congress and A State of Rebellion Declared

In May another Continental Congress assembled at Philadelphia. It was a more radical body than its predecessor. It included some distinguished newcomers, notably Benjamin Franklin, who had spent most of the previous eighteen years as agent for the Pennsylvania legislature in London, and Thomas Jefferson.

With little opposition the Congress voted to give full support to Massachusetts and to assume the direction of the war and the responsibilities of a central government. The New England militia were to become the nucleus of a continental army. On June 15, at the suggestion of John Adams, George Washington was appointed commander-in-chief.

Even at this stage of the American Revolution very few colonists were openly in favor of independence. But with the outbreak of war all British authority in the colonies rapidly disappeared in fact, if not in theory. The royal governors were ejected, the legislative assemblies of the different colonies assumed the powers of provincial congresses.

Committees of safety were appointed to carry on executive functions. Orders issued by these authorities were enforced by the local town and county committees, which had been set up by the First Continental Congress. Thus a new and essentially revolutionary government came into existence throughout the thirteen colonies.

Meanwhile, the British government ended the hesitation of the moderates by declaring the colonies in a state of rebellion at the end of 1775. All trade between the colonies and the mother country was interdicted. John Adams declared that this, “throws thirteen colonies out of the royal protection, and makes us independent in spite of supplications and entreaties.”Course of the American Revolution

The Declaration of Independence

As the war continued and the attitude of the British authorities made it more obvious that no concession could be expected, the idea of complete independence began to win more support. This was hastened by the publication of the pamphlet Common Sense in January 1776, written by the English immigrant Tom Paine.

Common Sense lived up to its title. Paine abandoned the legalistic arguments; the American had relied on before this, stating their case in terms of liberal idealism of the American Enlightenment. In clear and vigorous language he insisted that the colonies could govern themselves better than the British could do it for them.

He also had stated that they had a magnificent opportunity to create a new society, free from the tyranny and exploitation of the European background. The pamphlet was sold in hundreds of thousands and must have been read by almost every literate patriot.

At late as the autumn of 1775 the legislatures of five colonies went on record against independence. The groups who controlled the Middle Colonies continued to oppose it almost to the end. But in May 1776 the Continental Congress advised the colonies formally to establish independent governments.

In June, the Congress began discussion of a motion for independence, presented by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia. One of the strongest arguments for such a step was that it would make it easier for the Americans to secure help from France. A committee headed by Thomas Jefferson was appointed to draft a formal declaration. It was mainly Jefferson who wrote Declaration of Independence.

Lee’s motion was carried on July 2, with the support of every colony except New York. Declaration of Independence date was fixed on July 4. On the date, however, Declaration of Independence was adopted by the Congress, having also the signs of the New York delegates.

Jefferson’s task had been to give expression to the political sentiments generally held by his fellow-Americans. In simple and dignified terms the Declaration summarized the political philosophy characteristics of the Enlightenment:-- The belief that all men were endowed by God with inalienable rights,

- That governments were instituted in order to protect these rights,

- And that men could alter or abolish any government which became destructive of them.

The Americans had derived this theory mainly from John Locke. But Jefferson made one interesting change in Locke’s list of natural rights. Making no mention of the right of property, he spoke instead of “the pursuit of happiness,” thereby justifying the American Revolution in more liberal and more comprehensive terms.

Another significant feature of the Declaration of Independence was that, in listing the specific grievances of the colonies, Jefferson referred only to King George, not to Parliament. This was because the Continental Congress had now adopted the theory that Parliament had never had any legitimate authority over the colonies, the only legal tie with Great Britain being their allegiance to the Crown.

Conclusion

Thus the United States of America began its career as an independent nation with a ringing affirmation of faith in human rights. All men, according to the Declaration were “created equal,” and all governments derived “their just powers from the consent of the governed.” The traditional beliefs in hereditary inequalities and in authoritarian government was repudiated. The subsequent history not only of the United States but of the whole human race has consisted largely of an unending struggle to transform the ideals stated in the Declaration of Independence into effective realities.- Gipson L.H. (1954), The Coming of the Revolution.

- Miller J.C. (1943), Origins of the American Revolution.

- Andrews C.M. (1924), The Colonial Background of the American Revolution.

- Knollenberg B. (1960), Origins of the American Revolution, 1759-1766.

- Morgan E.S. (1956), The Birth of the Republic.

- Wright E. (1961), Fabric of Freedom.

- Alden J.R. (1954), The American Revolution.

Comments

Post a Comment