Development of Transportation during first American Industrial Revolution

The most conspicuous early manifestation of the Industrial Revolution in the United States of America were a series of new developments in transportation. Some of them, such as canal and hard-surfaced roads, were copied from Great Britain, while others, such as the steamboat, were native inventions.

The Question of Ownership

- Should these enterprises be under public ownership?

- Should they be left to private ownership?

- How far should government protect the public interest by regulating the rates and services, levied by private transport corporations?

Development of Transportation | First American Industrial Revolution

Roads and Bridges

The first hard-surfaced road in the United States was completed in 1794 and ran from Philadelphia to Lancaster, Pennsylvania. This inaugurated a period of road-building, about $40,000,000 being invested in new roads before 1812. With the notable exception of the National Highway, which was built by the Federal government, most of them were constructed and owned by private corporations, which expected to make profits on their investment by charging tolls. State governments chartered these corporations, frequently contributing a large part of their capital. Most of the early U.S. corporations were, in fact, formed for the building of roads and bridges.

In practice few of the roads brought any substantial profits. Most of the corporations, engaged in road construction quickly went out of business, and ownership then passed to the state governments.

On the other hand, some but not all of the bridge corporations, earned substantial revenues. Partly because their initial charters often gave them monopolistic rights. A notorious case was that of the Charles River Bridge Company, which had been chartered in 1786 to build a bridge across the Charles River from Boston to Massachusetts. During the next forty years this company made a profit amounting to thirty times its initial investment, while claiming that, according to its charter, no competing bridge could be built.

Popular resentment against such privileges, however, caused a gradual change of policy. In 1837 the United States Supreme Court disallowed the claim of Charles River Bridge Company and authorized the building of another bridge. To an increasing extent charters given to road and bridge corporations included a provision that when the original investment had been paid off, the projected work should become public property.Development of Transportation | First American Industrial Revolution

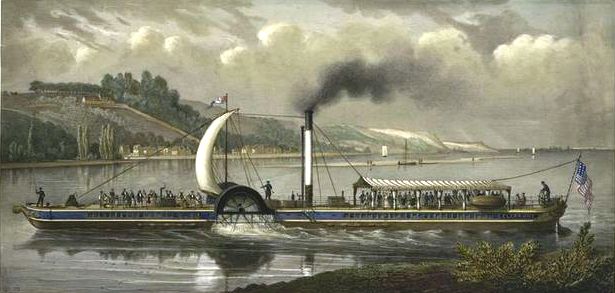

Steamboats

The second transportation improvement during first American Industrial Revolution was the steamboat, which was regularly used for inland waterways long before it replaced the sailing ship for ocean traffic. John Fitch had invented a practicable steamboat as early as the 1780’s. But the first person to make the idea commercially successful was Robert Fulton.

Fulton’s Clermont, launched in 1807, traveled up the Hudson from New York to Albany and back again in sixty two hours.

But it was on the Mississippi and its tributaries that steamboats were most widely used. The first Mississippi steamboat was built at Pittsburgh in 1811 by Nicholas Roosevelt. A special type of vessel was gradually evolved, capable of navigating in extremely shallow water, in heavy dew according to popular saying and providing luxurious accommodation for passengers. The period down to the American Civil War was the great age of Mississippi steamboating.

“In the age of the steamboat, as in the age of the automobile, it was an American characteristic to prefer speed to safety; fires, boiler explosions, and other catastrophes were not frequent, particularly when, as often happened.” By 1850 it was estimated that more than a thousand Mississippi steamboats had been destroyed, with a correspondingly heavy loss of life.

This caused the steamboat to become the first form of transportation to be subjected to Federal regulation. By the September Act of 1852, which marked a significant innovation in government policy, a safety code was prescribed and inspectors were to be appointed to enforce it.Development of Transportation | First American Industrial Revolution

Canals

After the Steamboat, the next innovation during the first American Industrial Revolution was the canal. The canal-building was inaugurated by the construction of Erie. The canal linked the Hudson River with Great Lakes and was built between 1817 and 1825 at a cost of about $8,000,000. The individual mainly responsible was DeWitt Clinton, two times Governor of New York.

Unlike the roads, Erie and a number of the later canals were built and owned by the state governments.

The completion of Erie Canal immediately cut freight rates from Buffalo to Albany from $100 to $10 a ton. Within a year it was bringing in $3,000,000 a year in tolls. It quickly paid for itself, and by providing cheap transportation between the Hudson and the West, caused a rapid growth in the wealth and importance of New York City. By 1850 nearly half of all American foreign trade was passing through New York.

The Erie was so astonishingly successful that other states plunged into a canal-building spree which ended unfortunately. Seaboard states planned competing links with the West, and Northwestern states set out to connect the Great Lakes with the Mississippi. Vast sums were borrowed by state governments, largely from European investors, while the Federal government gave assistance by making grants of public land.

But many of these plans were too ambitious; some of the money appears to have been wasted. And the Economic Depression of 1837 several states defaulted on their debts, causing immense indignation in Great Britain, to whose citizens most of these debts were owed.

In the end some of these canal projects had to be abandoned, and there was little further building after 1850, by which time about 4,000 miles of canals had been completed. It was partially because of this canal experience that the American people came to believe that private enterprise was generally more efficient and less extravagant than public ownership.Development of Transportation | First American Industrial Revolution

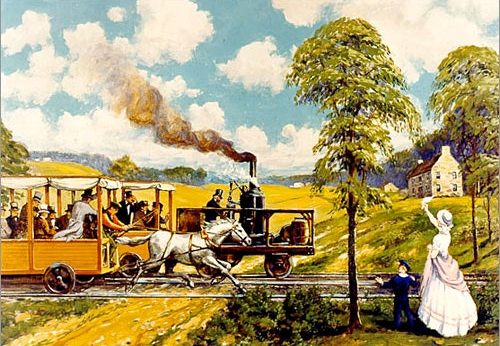

Railroads

Last and most important of the new internal transportation improvement during the First American Industrial Revolution was the railroad. Rail engines those were practicable devised during the 1820’s by both American and British inventors. The first American railroad was the Baltimore and Ohio, which began construction in 1828 and had enough track completed to run an engine over it by 1880. This was closely followed by Charleston and Hamburg, which was opened for passenger service in 1831. Trains traveled at the then dizzy rate of about twelve miles an hour.

All the early American railroads were constructed westwards from Atlantic seaboard cities. The cities of Boston, Philadelphia and Baltimore promoted lines in the hope of offsetting the advantages that New York had acquired from the Erie Canal, while in the South building was spurred by the commercial competition between Charleston and Savannah.

By 1850 a total of 8,879 miles had been completed, the best coverage being in New England. But almost all the lines were in the Eastern states, almost all of them ran from the coast inland and no lines had been completed connecting the Atlantic coast with any part of the trans-Appalachian country. Most of the railroad companies, moreover, controlled only a few miles of track, so that long-distance passengers had to make frequent changes from one line to another. The consolidation of different companies into large systems did not begin until after the mid-century.

“A few of the early railroads were state-owned; but the majority were built by private corporations, although until the financial crisis of 1837 much of the capital was contributed by state and municipal governments. Although the rates and services were subject to considerable state regulation, the railroads were usually allowed to make substantial profits and had little cause for complaint.”

Thus public policy was swinging back to the encouragement of private enterprise. This was due not only to the unfortunate canal experience but also to propaganda by businessmen and to the fact that capital was becoming more plentiful and could be raised more easily.Development of Transportation | First American Industrial Revolution

Conclusion

|

| Painting by Carl Rakeman |

- Cochran T.C. and Miller W. (1942), The Age of Enterprise.

- Taylor G.R. (1951), The Transportation Revolution.

- North D.C. (1961), The Economic Growth of the United States.

- Fishlow A. (1965), American Railroads and the Transformation of the Ante-Bellum Economy.

- Bruchey S. (1965), The Roots of American Economic Growth.

Comments

Post a Comment