How they sent the news of the completion of the Erie Canal to New York City; Franklin and Morse.

<<Previous Chapter | Full Book | Next Chapter>>

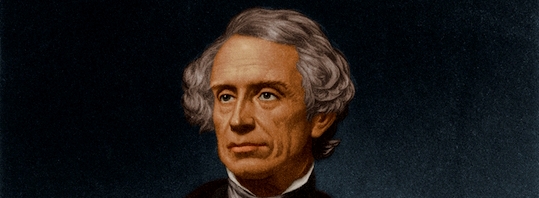

The first cannon was fired at Buffalo at ten o'clock in the morning; the last was fired at New York at half-past eleven. In an hour and a half the sound had travelled over five hundred miles. Everybody said that was wonderfully quick work; but to-day we could send the news in less than a minute. The man who found out how to do this was Samuel F. B. Morse.

We have seen how Benjamin Franklin discovered, by means of his kite, that lightning and electricity are the same. Samuel Morse was born in Charlestown, Massachusetts, about a mile from Franklin's birthplace, the year after that great man died. He began his work where Franklin left off. He said to himself, Dr. Franklin found out what lightning is; I will find out how to harness it and make it carry news and deliver messages.Morse becomes a painter; what he thought might be done about sending messages.

When Samuel Morse was a little boy, he was fond of drawing pictures, particularly faces; if he could not get a pencil, he would scratch them with a pin on the furniture at school: the only pay he got for making such pictures was some smart raps from the teacher. After he became a man he learned to paint. At one time he lived in France with several other American artists. One day they were talking of how long it took to get letters from America, and they were wishing the time could be shortened. Somebody spoke of how cannon had been used at the time of the opening of the Erie Canal. Morse was familiar with all that; he had been educated at Yale College, and he knew that the sound of a gun will travel a mile while you are counting five; but quick as that is, he wanted to find something better and quicker still. He said, Why not try lightning or electricity? That will beat sound, for that will go more than a thousand miles while you are counting one.What a telegraph is; a wire telegraph; Professor Morse invents the electric telegraph.

Some time after that, Mr. Morse set sail for America. On the way across the Atlantic he was constantly talking about electricity and how a telegraph*—that is, a machine which would write at a distance—might be invented. He thought about this so much that he could not sleep nights. At last he believed that he saw how he could make such a machine.

Suppose you take a straight and stiff piece of wire as long as your desk and fasten it in the middle so that the ends will swing easily. Next tie a pencil tight to each end; then put a sheet of paper under the point of each pencil. Now, if you make a mark with the pencil nearest to you, you will find that the pencil at the other end of the wire will make the same kind of mark. Such a wire would be a kind of telegraph, because it would make marks or signs at a distance. Mr. Morse said: I will have a wire a mile long with a pencil, or something sharp-pointed like a pencil, fastened to the further end; the wire itself shall not move at all, but the pencil shall, for I will make electricity run along the wire and move it. Mr. Morse was then a professor or teacher in the University of the City of New York. He put up such a wire in one of the rooms of the building, sent the electricity through it, and found that it made the pencil make just the marks he wanted it should; that meant that he had invented the electric telegraph; for if he could do this over a mile of wire, then what was to hinder his doing it over a hundred or even a thousand miles?

How Professor Morse lived while he was making his telegraph.

But all this was not done in a day, for this invention cost years of patient labor. At first, Mr. Morse lived in a little room by himself: there he worked and ate, when he could get anything to eat; and slept, if he wasn't too tired to sleep. Later, he had a room in the university. While he was there he painted pictures to get money enough to buy food; there, too (1839), he took the first photograph ever made in America. Yet with all his hard work there were times when he had to go hungry, and once he told a young man that if he did not get some money he should be dead in a week—dead of starvation.Professor Morse gets help about his telegraph; what Alfred Vail did.

But better times were coming. A young man named Alfred Vail* happened to see Professor Morse's telegraph. He believed it would be successful. He persuaded his father, Judge Vail, to lend him two thousand dollars, and he became Professor Morse's partner in the work. Mr. Vail was an excellent mechanic, and he made many improvements in the telegraph. He then made a model* of it at his own expense, and took it to Washington and got a patent* for it in Professor Morse's name. The invention was now safe in one way, for no one else had the right to make a telegraph like his. Yet, though he had this help, Professor Morse did not get on very fast, for a few years later he said, "I have not a cent in the world; I am crushed for want of means."

Professor Morse asks Congress to help him build a telegraph line; what Congress thought.

Professor Morse now asked Congress to let him have thirty thousand dollars to construct a telegraph line from Washington to Baltimore. He felt sure that business men would be glad to send messages by telegraph, and to pay him for his work. But many members of Congress laughed at it, and said they might as well give Professor Morse the money to build "a railroad to the moon."

Week after week went by, and the last day that Congress would sit was reached, but still no money had been granted. Then came the last night of the last day (March 3d, 1843). Professor Morse stayed in the Senate Chamber* of Congress until after ten o'clock; then, tired and disappointed he went back to his hotel, thinking that he must give up trying to build his telegraph line.

Miss Annie Ellsworth brings good news.

The next morning Miss Annie G. Ellsworth met him as he was coming down to breakfast. She was the daughter of his friend who had charge of the Patent Office in Washington. She came forward with a smile, grasped his hand, and said that she had good news for him, that Congress had decided to let him have the money. Surely you must be mistaken, said the professor, for I waited last night until nearly midnight, and came away because nothing had been done. But, said the young lady, my father stayed until it was quite midnight, and a few minutes before the clock struck twelve Congress voted* the money; it was the very last thing that was done.

Professor Morse was then a gray-haired man over fifty. He had worked hard for years and got nothing for his labor. This was his first great success. He doesn't say whether he laughed or cried—perhaps he felt a little like doing both.

The first telegraph line built; the first message sent; the telegraph and the telephone now.

When, at length, Professor Morse did speak, he said to Miss Ellsworth, "Now, Annie, when my line is built from Washington to Baltimore, you shall send the first message over it." In the spring of 1844 the telephone* line was completed, and Miss Ellsworth sent these words over it (they are words taken from the Bible): "What hath God wrought!"*

For nearly a year after that the telegraph was free to all who wished to use it; then a small charge was made, a very short message costing only one cent. On the first of April, 1845, a man came into the office and bought a cent's worth of telegraphing. That was all the money which was taken that day for the use of forty miles of wire. Now there are about two hundred thousand miles of telegraph line in the United States, or more than enough to reach eight times round the earth, and the messages sent bring in over seventy thousand dollars every day; and we can telegraph not only clear across America, but clear across the Atlantic Ocean by a line laid under the sea. Professor Morse's invention made it possible for people to write by electricity; but now, by means of the telephone, a man in New York can talk with his friend in Philadelphia, Boston, and many other large cities, and his friend listening at the other end of the wire can hear every word he says. Professor Morse did not live long enough to see this wonderful invention, which, in some ways, is an improvement even on his telegraph.

Comments

Post a Comment